Everything about the early bluesmen is speculative. Questions of authorship and transmission, the development of tunings and signature licks; even their dates and the arcs of their careers are subject to the confusions of oral tradition, the displacements and erasures of black history, a history of the negated. In the case of Robert Johnson, especially, history has had to contend with a myth-making apparatus geared up to broadcast the tale of an American Faust.

The story of Johnson selling his soul to the devil has been long dismissed by modern scholars, who generally follow Lomax’s claim that the legend was the inevitable result of a cultural climate in which “every secular black musician was, in the opinion of both himself and his peers, a child of the devil, a consequence of the black view of the European dance embrace as sinful in the extreme.”

Most sources now agree that in the winter of 1929 when Johnson disappeared from the jukes and roadhouses he frequented with Son House — the year when, according to the legend, Satan was tuning his guitar – Johnson travelled to Martinsville, Mississippi to sit at the feet of a local guitar master, Isaiah “Ike” Zimmerman. When he returned to House and his circle late in 1930 Robert Johnson was a musician transformed.

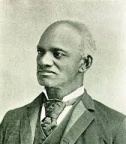

Only two photographs of Zimmerman survive: one taken in youth and one in old age. (Ike died in 1967.) Also several family traditions: that he was a doting father and family man, and that he, alone and later with his protégé, liked to practice his instrument at night in local cemeteries. This was not to channel the powers of darkness, of course, but to avoid waking Zimmerman’s many children when he played, sleepless, late at night. Blues historian Bruce Cornforth has identified numerous graveyards in the Martinsville-Hazelhurst area where Zimmerman and Johnson played, including Ike’s supposed favorite: the Beauregard cemetery, locally famous for its cypresses, off Highway 51.

Remarkably, in this most shadowy corner of black history something like scholarly consensus has been achieved. No devil, no magic – just a musician and his teacher seated atop Mississippi gravestones in the night, practicing the Blues. One question remains, however, and none of our sources has addressed it. Not Cornforth, not Wardlow, not Wald or Guaralnik. No one has considered what the dead thought of the music.

Word. Those backward-ass,

up-the-country niggaz

laying up there in the cold

cold ground would have

thought they heard

the devil.

And not some metaphorical,

Alan-Lomax, cultural-climate

kind of devil, but the real

devil-devil. Azriel or

Azazel or some

shit like that.

Those old Baptists

and Evangelicals laid

out in their pinewood overcoats,

figuring the train to Beulah-land

running just a little late, they

could tell you all about the devil.

And they’d be right, too, because

the devil just loves Mississippi.

And all those dead chumps,

looking up at the cypress roots

and hearing those blues,

they sure-enough didn’t hear

the same music that punk-ass

bitch Langston Hughes heard.

Langston Hughes had such

a hard-on for James Joyce

he tried to make the

blues into the uncreated

conscience of the Nee-gro

race.

But those dead people

didn’t hear the uncreated

conscience of their race.

They heard something that

chilled their shit, something

that sounded heathen.

What they surely heard

— through all the layers

of a soil that was done

trading sweat for cotton –

was two old boys playing

a music that was alive.

And those dead niggaz would

have hated that. Because

sweating, humping, moaning

and testifying, the blues are

alive. And the dead – well,

the dead are just fucked.

Isaac Mason is the name assumed by a person working under fraudulent credentials as a menial in a Chicago law firm. He lives, with many cartons of books, in a neighborhood where you would not feel comfortable.

Isaac Mason is the name assumed by a person working under fraudulent credentials as a menial in a Chicago law firm. He lives, with many cartons of books, in a neighborhood where you would not feel comfortable.